Walkers trudge past the ninth century Hindu temple complex at Prambanan, Central Java

This report is late… in fact more than four months late. This is because of culture shock, I tell myself. I’ve always thought walking was a minimalist, rather ascetic exercise. No frills. No hoop-la. But my mind has been blown to pieces by two days of walking in Java, and I’m having trouble reassembling it.

You see, I signed up for an event called the Jogjakarta International Heritage Walk (see http://www.jogjaheritagewalk.com/) held in November last year. It is one link in a chain of annual two-day walks held across the world under the umbrella of the International Marching League (IML) and the Internationaler Volkssportverband (IVV). I’ve taken part in these walks five or six times in Canberra Australia, and twice in Rotorua New Zealand. They have been quiet affairs run by volunteers, a bit amateurish, 100-300 walkers, a lone barbeque or sausage sizzle and a few cans of Coke for sale. The organisers will give you a free apple or a peppermint Mintie when you finish (if you’re lucky).

Now let me take you to a different planet. We are in Jogjakarta on the island of Java in Indonesia. Here the Two-Day Walk is all bright colours, swarms of people, deafening public address systems, gushing friendliness, mountains of food, countless uniformed volunteers, exotic dances, music, garish advertisements, endless photo-ops, dazzling local culture.

School children join in the 2019 Jogjakarta International Heritage Walk…

…soldiers from the Jogjakarta Palace too.

The welcome dinner, on the evening before the first day’s walking, was held in the ballroom of the swank Royal Ambarrukmo Hotel. There was a performance of sinuous classical Javanese dance amid long smorgasbord tables smoking with Indonesian food. An MC introduced the walkers country by country. He talked loud and fast in American-style English with all the over-the-top enthusiasm of a TV cookware salesman. There were big groups from Denmark, the Netherlands, Japan and France, plus many smaller groups and individuals from other parts of the world, including a few bewildered Australians and New Zealanders cowering at the back of the enormous, brightly lit hall.

The pre-walk welcome dinner… just a simple snack in austere surroundings.

“Tomorrow, breakfast is at 4:00 am,” the MC shouted. “And be ready to board buses to our starting point at 5:00 am!”

He added a menacing reminder. “And don’t forget… on the first day of walking you wear the green T-shirt… I repeat, the GREEN one, not the orange one!”

We checked our event bags. Yes, we each received two Heritage Walk T-shirts, one dark green, the other bright orange. The following morning, obediently resplendent in my green T-shirt beautifully decorated with the head of shadow-play hero Karno, I boarded a bus with other walkers, and we headed for the ninth century Hindu temple complex at Prambanan, about 25 kilometres from Jogjakarta.

Australians were made to feel very welcome (like every other nationality).

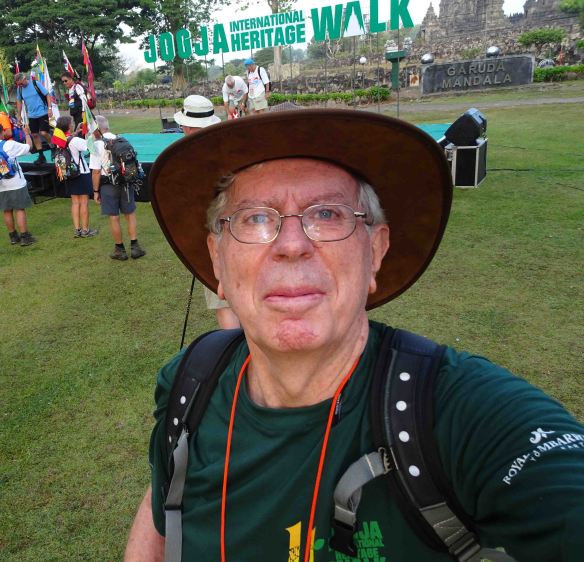

I’m ready to go… a selfie at 6:00 a.m. in the morning.

With the ancient stone temples lowering in the background, we crowded around the start gate, and at 6:00 a.m. sharp, swarmed through it onto a paved path that took us into neighbouring fields and villages. The walking was easy, not too hot at that early hour, and immensely enjoyable. For a short time we were accompanied by a platoon of guards dressed in traditional Javanese military costume. In the densely farmed fields farmers (more women than men) were bent double weeding and harvesting their chilli plants. On the roadside, raw rice lay drying in the sun, spread out on grass mats as farmers turned the grains with wooden rakes. We squeezed past a trackside threshing operation. Sheaves of newly harvested rice were being fed into a chugging machine which, like a small fountain, spouted raw grains into sacks.

Walkers squeeze past a trackside rice-threshing operation, and (below)…

…newly harvested rice lies drying in the morning sun.

The path skirted an archaeological excavation. As if coming up for air after centuries underground, a Hindu temple-monument – Candi Kedulan – looked up from the bottom of a large, freshly dug gash in the earth. It was in a remarkably sharp state of preservation, probably protected – like Pompeii – by a shroud of volcanic ash from a forgotten eruption a millennium ago. Already paving was being put in place to accommodate future fee-paying visitors.

The world of a thousand years ago keeps emerging from the under the earth: Candi Kedulan.

A few kilometres on and I completed the ten kilometre circuit, arriving back in the precinct of Candi Prambanan having covered the distance in a sweaty but leisurely three hours. You might also have chosen a twenty kilometre circuit or a five kilometre circuit. The latter was popular with a remarkable cohort of geriatric Japanese, some with question-mark spines, stringy legs, and very wobbly knees, but also with steely determination to complete their quota of five kilometres.

One woman, probably in her nineties, stumbled and fell. As her companions and Indonesian volunteers crowded around to help her, she fended them off. She rolled on to her hand and knees, folded her legs carefully under her, gripped a walking pole, and levered herself slowly to her feet. She (like many other Japanese walkers) was wearing white cotton gloves. These were now stained with dirt and blood, but she pushed away would-be helpers and walked on (not very steadily) with a defiant look in her eye.

A sinuous, ultra-slow classical Javanese dance performed for walkers by highschool students.

Walkers were greeted at the finish by loudspeakers and entertainment, mostly traditional dances performed on a makeshift stage or on the grass by children excited to be dressed up and showing off. As we watched them we tucked into a simple but delicious Indonesian brunch. We got plied with sweet, psychedelically coloured, rice-cakes too, even thick slices of watermelon dripping with red juice.

Ahhh… the rigours of walking, Indonesian style.

Day Two. Again we were up and gnawing on an extravagant hotel breakfast at 4:00 am. At five o’clock we were in a bus, this time wearing our bright orange T-shirts. As the sky began to glow the bus headed up a steep road to the upper slopes of cone-shaped Mount Merapi. Merapi is one of the most active volcanoes in the world, erupting on average every six to eight years. When it erupted in 2010 more than 300 people lost their lives and a big gash was blasted in the side of the summit.

Obediently wearing our orange T-shirts, we prepare to walk up towards the summit of Merapi.

If the mountain erupts, we’re okay. There are special concrete shelters for protection against ash. (But what about hot gas… and big boulders?)

The day was overcast and the early morning air cool at our starting point in the village of Poncoh, about ten kilometers below the summit. At 6:00 a.m. we jostled on to a narrow road that sloped sharply upwards. We walked into a garland of brilliant green: coconut groves, palm oil plantations, second-growth forest. The walking was easy, but the angle of the road quickly dampened our T-shirts with sweat.

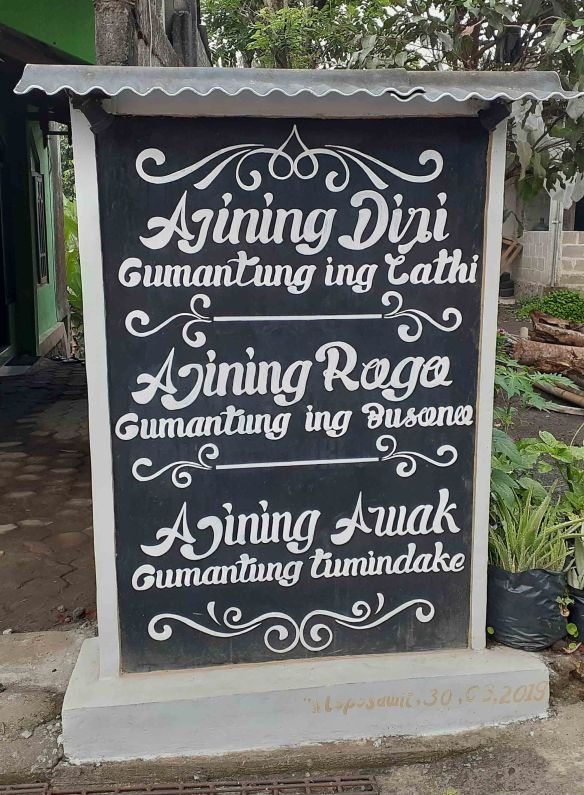

Roadside declarations of cultural/religious orientation. Almost all the people of the mountain are strong Muslims, but Java’s treasury of aphoristic wisdom remains strong too. The plaque reads: “Your personal honour depends on how you speak; Your personal appearance depends on what you wear; Your personal reputation depends on how you behave.”

The path took us through poor but neat villages with friendly people emerging from their houses to enjoy the exotic spectacle of foreigners puffing past, some pushing themselves along with walking poles. Many villagers offered us salak (snakeskin) fruit from their own trees, and coconut milk chopped on the spot from freshly picked nuts. Of course there was the usual price to pay – selfie photos amid a vortex of children and laughter. Can there be – anywhere in the world – more spontaneously friendly and generous people?

For once in my life, I’m the best-looking bloke in a photograph.

The circuit brought me back to Poncoh Village around 9:30, three and a half hours later. But the fitness band on my wrist told me I had walked quite a lot further than ten kilometres: 13.26 kilometres to be precise. The distance had passed in a flash. An hour later we were handed a delicious early lunch in a cardboard box. Local children, conducted by their teachers, demonstrated traditional games. These included a kind of dance like the better-known Filipino tinikling. Four bamboo poles were laid on the ground like a hash-tag icon (#), the end of each pole gripped by a kneeling child. Each pair of poles was clapped together alternately in rhythm with a folk tune while other children danced with delicate steps in and out of the spaces appearing momentarily between the poles. (For a stage version of this dance with its nail-biting precision take a look at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lRX_tEJBj5c ) Meanwhile other children fanned out among the walkers trying to practise their English. Given whispered encouragement by their teachers, each was clutching an exercise book with model sentences in it. Some of the French walkers were a bit bewildered. Their English wasn’t much better than the children’s, but they did their best with plenty of laughter.

Local students (supervised by their teacher at rear) perform a tricky folk dance. One wrong step and… A metaphor, perhaps, for the ruthless rigidity of Javanese society?

Eleven year old Nur, clutching her prompt sheets, practises English with me.

That night the event closed with an elaborate dinner in a broad pendopo pavilion open to the warm tropical air. It was the usual Indonesian amalgam of rigid formality and laughter-filled informality. A small band played kroncong music, a genre born out of Java’s distant connection with Portugal. The music flowed with noctural tenderness from a violin, flute, ukulele, guitar and cello. (Get a small taste of this simple, beautiful music at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a8lKKOypnMU )

Each walker was summoned – together with other walkers from the same country – to receive a diploma and the Two-Day Walk medal. To the accompaniment of gentle kroncong music and the flash of a hundred smart-phone cameras, I too ducked my head as the ribbon was placed around my neck.

Indonesia does walking its own way, and after putting aside my culture shock… I like it!

At the closing dinner, I show off my medal.